Create a simple page

As in previous exercises, we start off by creating a simple Flask app in a single app.py file.

For this exercise, though, I'm including an <iframe> tag which will bring in a YouTube video:

from flask import Flask

app = Flask(__name__)

@app.route('/')

def homepage():

return """

<h1>Hello world!</h1>

<iframe src="https://www.youtube.com/embed/YQHsXMglC9A" width="853" height="480" frameborder="0" allowfullscreen></iframe>

"""

if __name__ == '__main__':

app.run(debug=True, use_reloader=True)

Here's what http://localhost:5000 looks like:

Basically, a webpage with an embedded YouTube video on it. YouTube will be doing the neat part – supplying entertaining video – and for the rest of this lesson, we'll practice what we've learned about basic Flask apps and HTML so far.

Hello, embeds

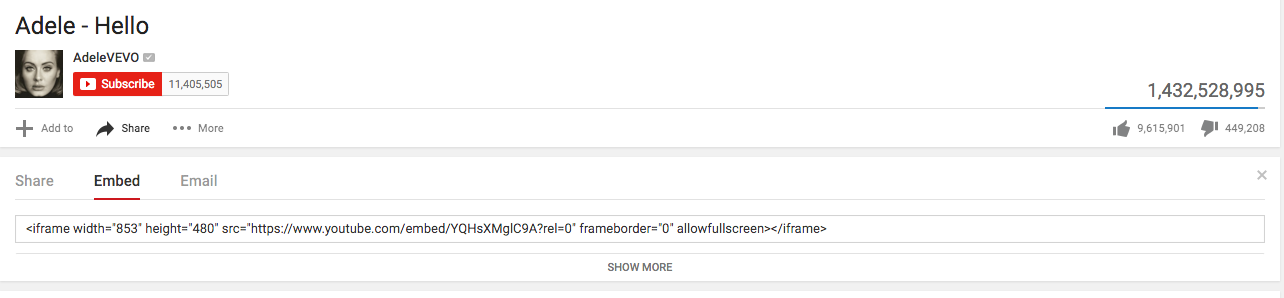

You might already know how to get the embed code for a YouTube video. But let's walk through it.

Go to any YouTube video page: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YQHsXMglC9A

Look for the menu of sharing options. Click the Embed option to reveal an HTML snippet that you copy and paste into a webpage:

This is the code YouTube provides

<iframe width="853" height="480" src="https://www.youtube.com/embed/YQHsXMglC9A" frameborder="0" allowfullscreen></iframe>

I like to rearrange the attributes, so that the src attribute comes first:

<iframe src="https://www.youtube.com/embed/YQHsXMglC9A" width="853" height="480" frameborder="0" allowfullscreen></iframe>

Either way, when that snippet is rendered by the web browser, it looks like this:

YouTube's embed URL pattern

There are two kind of YouTube URLs to be aware of (for now):

The URL for the standard video page:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VIDEOID

And the embed URL for that same video:

https://www.youtube.com/embed/VIDEOID

In the <iframe> HTML tag, note the value of the src attribute is a URL. For a YouTube video, that's where you use the embed version. However, you can visit the embed URL just as if it were any other URL, and it will take you to what basically amounts as a full-page view of the video:

https://www.youtube.com/embed/YQHsXMglC9A

The last component of the URL – YQHsXMglC9A – is YouTube's unique identifier for the video. And the standard YouTube video URL uses that identifier as well, as the value to the URL attribute of v, e.g. v=YQHsXMglC9A:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YQHsXMglC9A

So basically, given that the pattern for an embed URL for any YouTube video is this:

https://www.youtube.com/embed/UNIQUE_YOUTUBE_ID

Just replace UNIQUE_YOUTUBE_ID with the YouTube unique identifier for any YouTube video you like.

The <iframe> tag

This is a segue; if you already know what iframes are, feel free to skip to the next section.

An iframe is a HTML tag that basically embeds a remote webpage inside the current webpage. The source of the embedded webpage is at the URL specified in the src attribute.

The video site Vimeo has a similar design. For example, the video at this following Vimeo URL:

Can be embedded with this HTML snippet, which is an <iframe> tag as well as some extra HTML to show a hyperlink:

<iframe src="https://player.vimeo.com/video/105955605" width="500" height="281" frameborder="0" webkitallowfullscreen mozallowfullscreen allowfullscreen></iframe>

<p><a href="https://vimeo.com/105955605">Mary live-codes a JavaScript game from scratch – Mary Rose Cook at Front-Trends 2014</a> from <a href="https://vimeo.com/fronttrends">Front-Trends</a> on <a href="https://vimeo.com">Vimeo</a>.</p>

Note its src attribute is also a URL:

https://player.vimeo.com/video/105955605

Or you could opt to include much simpler pages:

<iframe src="http://www.example.com/" width="500" height="300" frameborder="0"></iframe>

Note that some websites will block this behavior – try embedding https://www.google.com onto a webpage.

The problem with iframes that, when they work, you have to load all of the HTML specified by that other website. On the other hand, for complex things such as, well videos, they are often the easiest way to show that kind of content on your webpages without actually hosting it and/or developing the video-player code yourself.

We're using iframes for now just because it's fun; don't think that you can easily build useful applications just by clobbing together other sites via iframes.

Adding a dynamic /videos path

Let's a /videos path with a variable part at the end: the YouTube video ID. It can return nearly the same HTML as the homepage code, except we'll use the string.Template class to create a templated string, and then use substitute() to add in the variable part.

Remember to include string.Template via an import statement at the top.

All together:

from flask import Flask

from string import Template

app = Flask(__name__)

@app.route('/')

def homepage():

return """

<h1>Hello world!</h1>

<iframe src="https://www.youtube.com/embed/YQHsXMglC9A" width="853" height="480" frameborder="0" allowfullscreen></iframe>

"""

@app.route('/videos/<vid>')

def videos(vid):

vidtemplate = Template("""

<h2>

YouTube video link:

<a href="https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=${youtube_id}">

${youtube_id}

</a>

</h2>

<iframe src="https://www.youtube.com/embed/${youtube_id}" width="853" height="480" frameborder="0" allowfullscreen></iframe>

""")

return vidtemplate.substitute(youtube_id=vid)

if __name__ == '__main__':

app.run(debug=True, use_reloader=True)

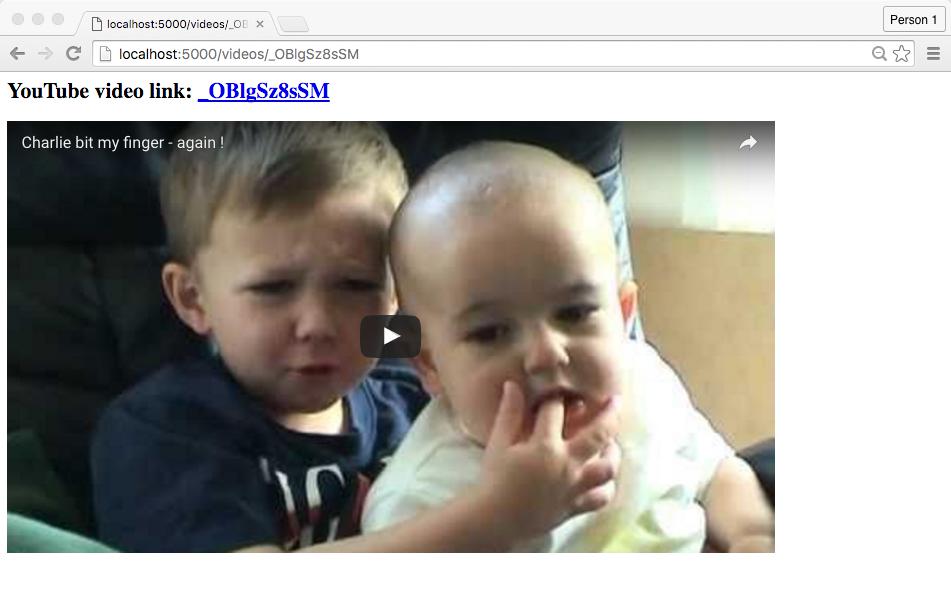

And now visiting localhost:5000/videos/ with a YouTube video ID appended to it will show a page with the embed:

Before moving on, let's refactor that redundant HTML code and move it to the top, e.g. to a variable named HTML_TEMPLATE

from flask import Flask

from string import Template

HTML_TEMPLATE = Template("""

<h2>

YouTube video link:

<a href="https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=${youtube_id}">

${youtube_id}

</a>

</h2>

<iframe src="https://www.youtube.com/embed/${youtube_id}" width="853" height="480" frameborder="0" allowfullscreen></iframe>""")

app = Flask(__name__)

@app.route('/')

def homepage():

vidhtml = HTML_TEMPLATE.substitute(youtube_id='YQHsXMglC9A')

return """<h1>Hello world!</h1>""" + vidhtml

@app.route('/videos/<vid>')

def videos(vid):

return HTML_TEMPLATE.substitute(youtube_id=vid)

if __name__ == '__main__':

app.run(debug=True, use_reloader=True)

Adding YouTube URL embed parameters

Generally, you have very limited ways to customize the appearance of an iframe. YouTube has a few options you can add to the src URL's query string, documented on its page, YouTube Embedded Players and Player Parameters

Note: If you’re unfamiliar with the concept of a URL query string, read up on their basics at Wikipedia. This is a HTTP concept, not anything to do with the Python language

For example, if you want a video to start 30 seconds in, you can include the start parameter and set it to a value of 30:

For example, if you want a video to autoplay, add the autoplay parameter to the embed URL and set it to a value of 1:

https://www.youtube.com/embed/mP1cRqZ8JGw?autoplay=1

Note: the autoplay parameter, among others, won’t work for the Adelle “Hello” video if you attempt to directly visit the embed code:

https://www.youtube.com/embed/YQHsXMglC9A?autoplay=1

– as apparently its publisher does not want its videos to autoplay upon a direct visit to the embed URL. You’ll find this restriction on a lot of commercial video. That doesn’t really impact the way we do embeds via iframes, just wanted to point out this kind of YouTube-specific behavior…

To make a video autoplay, and start at 90 seconds in, and loop continuously, tack on the start and loop parameters. You can view it in action at this URL:

https://www.youtube.com/embed/mP1cRqZ8JGw?autoplay=1&start=90&loop=1

You can read about the other options at YouTube's documentation. Note that these only work with YouTube embeds. I'm showing this as just an example of the kind of limited customization you can do – anything more complex requires working programatically with the YouTube API, something that is its own topic.

How to deal with missing/non-existent YouTube videos

Right now, our app isn't too exciting. I mean, why go to:

http://localhost:5000/videos/mP1cRqZ8JGw

When you could just go straight to YouTube itself:

https://www.youtube.com/embed/mP1cRqZ8JGw

– and forgo the trouble of creating a mini-web app?

Fair question. So let's first differentiate our app by customizing how it acts when you refer to a non-existent video ID, i.e. try to embed a video URL that doesn't exist.

Here's how YouTube does it:

https://www.youtube.com/embed/BLAHBLAHBLAH

Let's try to do something different, such as sending the user to some other video that does work.

Detecting a valid YouTube video ID

So, how do we tell if a given YouTube video ID actually refers to a real video?

First, it's important to realize that everything we do in this subsection is just "regular" Python scripting. Nothing about it has anything inherent to do with building a Flask app. This section will make more sense to you if you know a bit about how HTTP works or have done web scraping before. If you haven't, just follow along.

By now, you should be familiar with the Requests library, which is a library we use to download files from the Internet:

import requests

resp = requests.get('http://www.example.com')

Inherent to "downloading" a file is the process of making a HTTP request, and getting a response. But usually, when people talk about "downloading" a file, they mean to make a request for a URL and save the content (or body) of its response to the hard drive.

For example, the following snippet will save the (text) content of http://www.example.com to a local file named example.html:

import requests

resp = requests.get('http://www.example.com')

with open('example.html', 'w') as f:

f.write(resp.text)

The status code of a HTTP response

But there's more to a HTTP response than its content. The requests.Response object (resp, in the variable name above) contains plenty of other attributes, the most relevant one to us being status_code.

Try the following from the interactive Python shell:

import requests

resp = requests.get('https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mP1cRqZ8JGw')

resp.status_code

# 200

The status code of 200 amounts to the webserver saying everything is "OK".

So what is the status code when a video ID isn't valid?

Try the same code, but use an obviously fake YouTube ID:

import requests

resp = requests.get('https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LOREMIPSUM')

resp.status_code

# 404

The dreaded 404 status code, i.e. "Not Found", is what a web server returns when you visit a non-existent URL.

Note that most modern websites are configured to return a webpage even when a URL doesn't correspond to an existing resource, so sometimes it's hard to tell that what you're getting is an actual 404 response.

Here's YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LOREMIPSUM

Some sites, like Bloomberg.com, will make it much more obvious that the rendered webpage you're receiving is an actual 404 page:

http://www.bloomberg.com/loremipsum

Writing a status_code-testing function

So now we have a Python routine which can determine whether any given URL (YouTube or whatever) actually exists

import requests

some_url = 'https://www.youtube.com'

resp = requests.get(some_url)

if resp.status_code == 200:

print("OK")

else:

print("Not OK")

Abstract that to a function (and assume that import requests is at the top of the file). And also, instead of using Requests get() method, let's use head(), which attempts to do a lightweight request. We don't need the entire web response, just its metadata, i.e. its "head". You can read more about HTTP request types, including HEAD, on Wikipedia:

def is_url_ok(url):

resp = requests.head(url)

if resp.status_code == 200:

return True

else:

return False

Or, to be even more concise:

def is_url_ok(url):

resp = requests.head(url)

return 200 == resp.status_code

Or, to be even more concise, in such a way that it isn't too unreadable:

def is_url_ok(url):

return 200 == requests.head(url).status_code

Either way, if all we cared about was testing a bunch of random URLs, here's how this function would be used:

import requests

def is_url_ok(url):

return 200 == requests.head(url).status_code

ARTICLE_NAMES = ['Han_Solo', 'Han_shot_first', 'Greedo', 'Greedo_shot_second']

for aname in ARTICLE_NAMES:

url = 'https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/' + aname

is_ok = is_url_ok(url)

print(is_ok, url)

# True https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Han_Solo

# True https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Han_shot_first

# True https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Greedo

# False https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Greedo_shot_second

Incorporating the URL status check in a Flask app

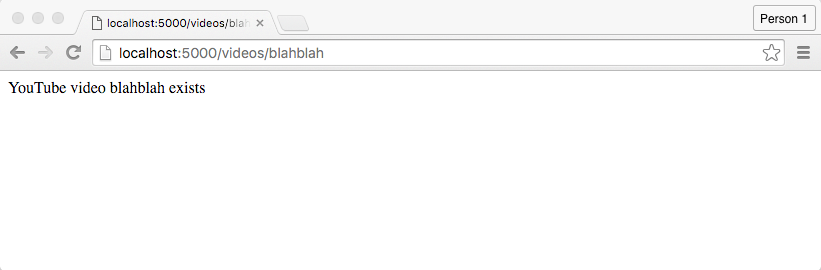

Let's forget the HTML part for now. Let's just create a basic Flask app that returns "YouTube video [youtube ID] exists" for a valid YouTubeID, and a different message if it does not exist.

Create a skeleton Flask app as we've done many times before with a /videos route that can take a variable:

from flask import Flask

app = Flask(__name__)

@app.route('/videos/<id>')

def videos_page(id):

return "YouTube video {video_id} exists".format(video_id=id)

if __name__ == '__main__':

app.run(debug=True, use_reloader=True)

Obviously, it's always going to return the same message no matter what you put in as <id> in the path:

http://localhost:5000/videos/blahblah

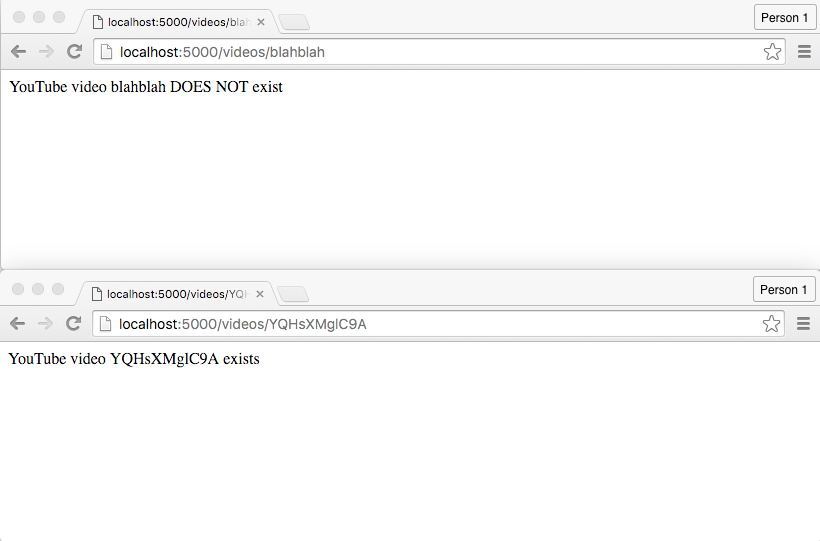

Now, let's throw in the implementation of the is_url_ok() function, including the importing of the Requests library. Again, app.py is just a Python script that has some Flask conventions. We can add non-Flask Python code to it as we wish…though we do need to define the is_url_ok() function before it gets referred to:

from flask import Flask

import requests

def is_url_ok(url):

return 200 == requests.head(url).status_code

app = Flask(__name__)

@app.route('/videos/<id>')

def videos_page(id):

youtube_url = 'https://www.youtube.com/watch?v={video_id}'.format(video_id=id)

if True == is_url_ok(youtube_url):

return "YouTube video {video_id} exists".format(video_id=id)

else:

return "YouTube video {video_id} DOES NOT exist".format(video_id=id)

if __name__ == '__main__':

app.run(debug=True, use_reloader=True)

(Note: in more advanced web applications, ancillary code will all be in a separate file, not thrown into app.py, because throwing everything into a single application file can get messy.)

Now our web app's /videos path can respond to valid and invalid YouTube IDs differently:

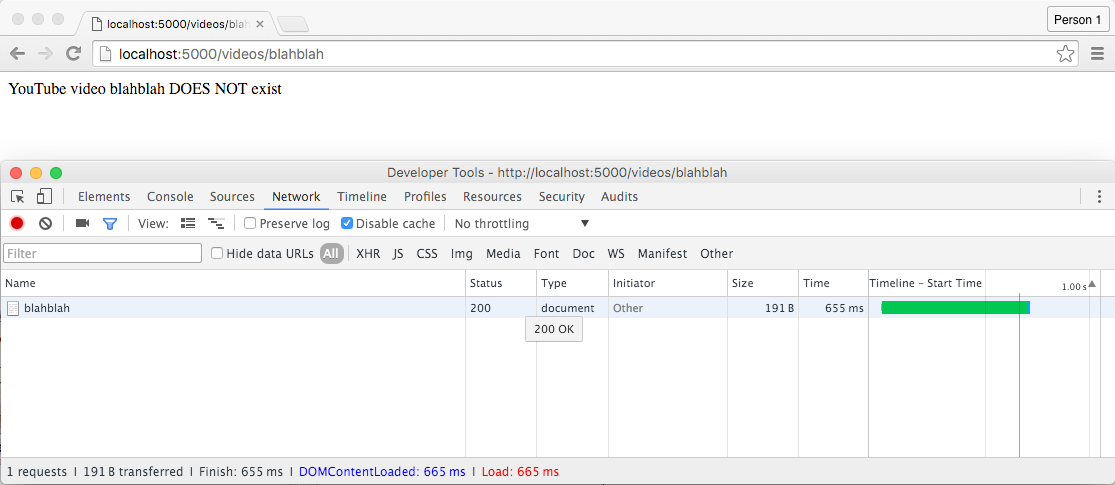

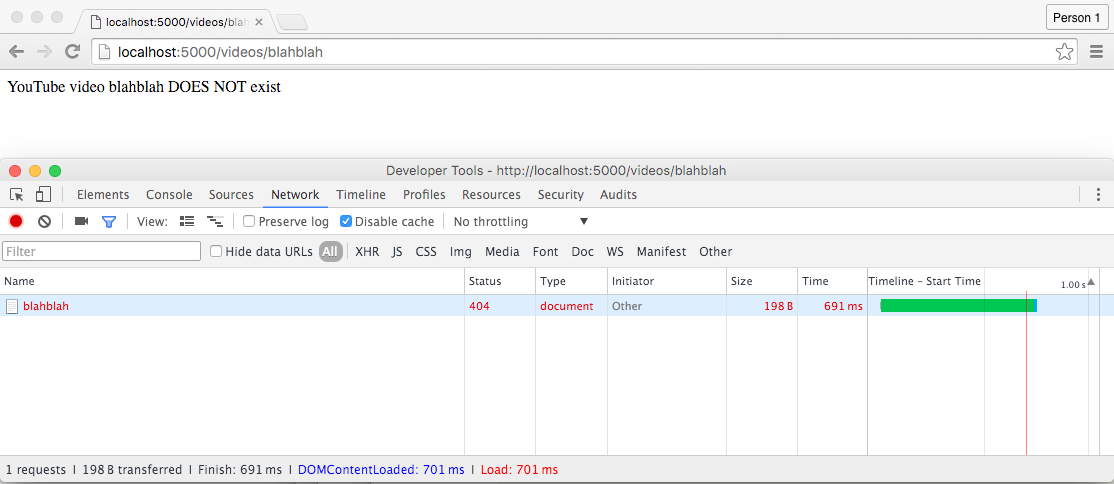

Returning a 404 status code in Flask

Note that while we've configured our web app to return a different message based on the result of the is_url_ok() function call…our web app technically returns an "OK" response to the user. You can check this via your browser's dev tools network panel:

Or, if you don't know how to use your browser's dev tools yet, you can pop open a new Terminal window and hit up your own web server via ipython and Requests:

import requests

resp = requests.get("http://localhost:5000/videos/blahblah")

print(resp.text)

# => YouTube video blahblah DOES NOT exist

print(resp.status_code)

# => 200

Whether our app returns the proper status code is a fairly inconsequential detail at our current level of web app development. But because it's so simple to pick the desired status code to return for a given route, we'll do it:

In a given view function, you can manually specify the status code of the response by return a second value. Here's a simplified version:

@app.route('/')

def homepage():

return "Whatever", 404

For our current app, this is what that would look like – note that we don't have to specify 200 for the OK case, because the status code is 200 by default:

@app.route('/videos/<id>')

def videos_page(id):

youtube_url = 'https://www.youtube.com/watch?v={video_id}'.format(video_id=id)

if True == is_url_ok(youtube_url):

return "YouTube video {video_id} exists".format(video_id=id)

else:

html = "YouTube video {video_id} DOES NOT exist".format(video_id=id)

return html, 404

Here's what that change looks like in the dev tools network panel:

Test the change for yourself in ipython:

import requests

resp = requests.get("http://localhost:5000/videos/blahblah")

print(resp.text)

# => YouTube video blahblah DOES NOT exist

print(resp.status_code)

# => 404

All together

Whew, that was a lot of code and concepts. Let's take what we've written so far, but go back to using iframes to embed YouTube videos…because printing "YouTube video YQHsXMglC9A exists" makes for a very boring web app.

See if you can write the entirety of app.py without looking at my solution, which I've changed around to fit my tastes, including having the homepage route render just a simple "Hello world" message for now:

from flask import Flask

from string import Template

import requests

def is_url_ok(url):

return 200 == requests.head(url).status_code

IFRAME_TEMPLATE = Template("""

<iframe src="https://www.youtube.com/embed/${youtube_id}?autoplay=1" width="853" height="480" frameborder="0" allowfullscreen></iframe>""")

app = Flask(__name__)

@app.route('/')

def homepage():

return "Hello world"

@app.route('/videos/<vid>')

def videos(vid):

youtube_url = 'https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=' + vid

if True == is_url_ok(youtube_url):

hed = """<h2><a href="{url}">YouTube video: {id}</a></h2>""".format(url=youtube_url, id=vid)

iframe = IFRAME_TEMPLATE.substitute(youtube_id=vid)

else:

# when the youtube video id is not found

hed = """<h2>Youtube video {id} <strong>does not exist</strong></h2>""".format(id=vid)

# note that we substitute a specific YouTube ID for the template

iframe = IFRAME_TEMPLATE.substitute(youtube_id='dQw4w9WgXcQ')

return hed + iframe

if __name__ == '__main__':

app.run(debug=True, use_reloader=True)

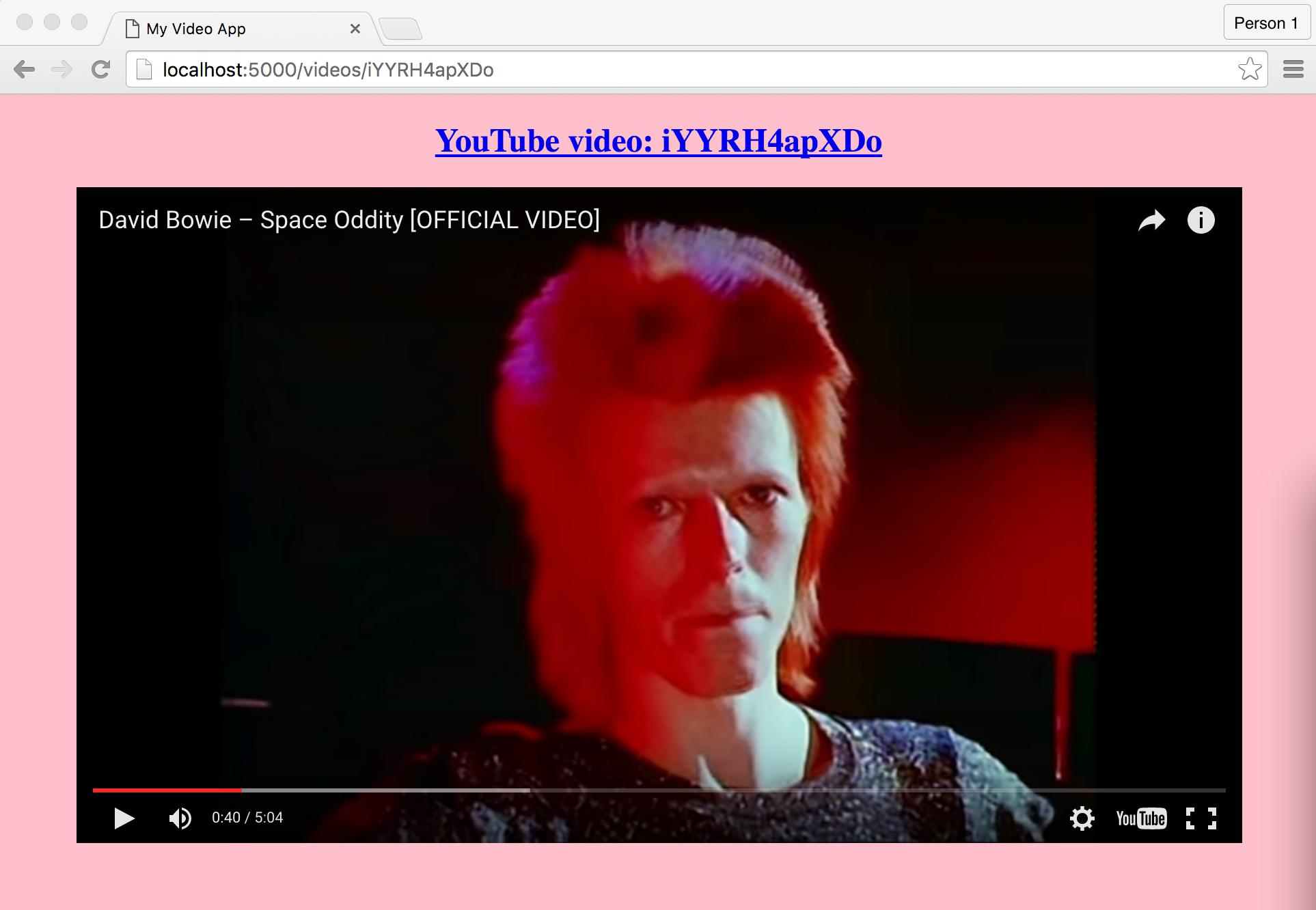

All together, as a full webpage

The app code above works, but let's change it so that it outputs a "proper" webpage, with <head> and <body> tags, among other common structural tags.

The main change is to make a single Template that has all of the HTML. Here's what it could look like:

HTML_TEMPLATE = Template("""

<!DOCTYPE html>

<head>

<title>My Video App</title>

</head>

<body>

<h2>${headline}</h2>

<iframe src="https://www.youtube.com/embed/${youtube_id}?autoplay=1" frameborder="0" allowfullscreen></iframe>

</body>""")

Note that it has two place holder variables: ${headline} and ${youtube_id}. This is because the two different views in our app – one for a valid YouTube video id and one for the 404-rickroll – have pretty much the same code except for the headline.

Here's what their view function code looks like, with the use of HTML_TEMPLATE as shown above. Note how the headline HTML is processed first, then inserted into the Template referred to by HTML_TEMPLATE, which is stuffed into a variable named all_html.

@app.route('/videos/<vid>')

def videos(vid):

youtube_url = 'https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=' + vid

if True == is_url_ok(youtube_url):

hed = """<a href="{url}">YouTube video: {id}</a>""".format(url=youtube_url, id=vid)

all_html = HTML_TEMPLATE.substitute(headline=hed, youtube_id=vid)

else:

hed = """YouTube video <u>{id}</u> does not exist""".format(id=vid)

all_html = HTML_TEMPLATE.substitute(headline=hed, youtube_id='dQw4w9WgXcQ')

return all_html

This could be better refactored, but you get the point.

All together, with CSS

As I've mentioned before, CSS, the language used to style webpages, is, well, its own language, with entirely different syntax from HTML and Python. It's beyond the scope of our lessons, though, Scott Murray has an excellent primer on CSS in his Interactive Data Visualization book.

CSS is generally kept in files separate from HTML (and most definitely from app.py). But for now, we'll add the CSS code into the HTML template, using the <style> tag.

The following CSS code, as inserted into HTML_TEMPLATE, sets some style attributes of the <body> tag, which is the tag that contains all visible elements in our HTML. The <style> tags themselves generally go within the <head> tags:

HTML_TEMPLATE = Template("""

<!DOCTYPE html>

<head>

<title>My Video App</title>

<style>

body{

text-align: center;

background-color: pink;

}

</style>

</head>

<body>

<h2>${headline}</h2>

<iframe src="https://www.youtube.com/embed/${youtube_id}?autoplay=1" frameborder="0" allowfullscreen></iframe>

</body>""")

The only new tag in the HTML is <style>, which encloses this CSS snippet:

body{

text-align: center;

background-color: pink;

}

Everything else about app.py remains the same. But the addition of style code changes what the webpage looks like, even though nothing about the content has changed:

http://127.0.0.1:5000/videos/iYYRH4apXDo

Note that because the HTML template is shared across both the 200 and 404 view code, our 404-page will have the same styling:

http://127.0.0.1:5000/videos/thisisbad

OK, it's not terribly pretty, but we've barely begun to dig into CSS styling.

All together, spinning around

One more example of how CSS works in practice.

Let's clean up the <iframe> tag. Instead of this:

<iframe src="https://www.youtube.com/embed/${youtube_id}?autoplay=1" width="853" height="480" frameborder="0" allowfullscreen></iframe>

We remove the width and height attributes:

<iframe src="https://www.youtube.com/embed/${youtube_id}?autoplay=1" frameborder="0" allowfullscreen></iframe>

And we set those properties in the CSS within the <style> tag:

iframe{

width: 80%;

height: 600px;

}

It's almost always preferable to set style attributes in the kind of CSS syntax above, rather than inside the actual HTML tag.

And what the heck, we'll add a bunch of (relatively) new CSS style attributes that govern animation of elements. I won't even try to explain their syntax, though here are some relevant links:

Here's the complete code for app.py with most of the code now in the HTML template – and this is why we will eventually move all HTML view code into its own files, out of app.py:

from flask import Flask

from string import Template

import requests

def is_url_ok(url):

return 200 == requests.head(url).status_code

HTML_TEMPLATE = Template("""

<!DOCTYPE html>

<head>

<title>My Video App</title>

<style>

body{

text-align: center;

background-color: #FFAAAA;

}

iframe{

width: 80%;

height: 600px;

-webkit-animation: fun-function 2.5s linear infinite;

-webkit-animation-direction: alternate;

-moz-animation: fun-function 2.5s linear infinite;

-moz-animation-direction: alternate;

}

@-webkit-keyframes fun-function{

from{

-webkit-transform: rotate(0deg) skew(-30deg);

}

to{

-webkit-transform: rotate(360deg) skew(30deg);

}

}

@-moz-keyframes fun-function{

from{

-moz-transform: rotate(0deg) skew(-30deg);

}

to{

-moz-transform: rotate(360deg) skew(30deg);

}

}

</style>

</head>

<body>

<h2>${headline}</h2>

<iframe src="https://www.youtube.com/embed/${youtube_id}?autoplay=1" frameborder="0" allowfullscreen></iframe>

</body>""")

app = Flask(__name__)

@app.route('/')

def homepage():

return "Hello world"

@app.route('/videos/<vid>')

def videos(vid):

youtube_url = 'https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=' + vid

if True == is_url_ok(youtube_url):

headline_html = """<a href="{url}">YouTube video: {id}</a>""".format(url=youtube_url, id=vid)

all_html = HTML_TEMPLATE.substitute(headline=headline_html, youtube_id=vid)

else:

headline_html = """YouTube video <u>{id}</u> does not exist""".format(id=vid)

all_html = HTML_TEMPLATE.substitute(headline=headline_html, youtube_id='dQw4w9WgXcQ')

return all_html

if __name__ == '__main__':

app.run(debug=True, use_reloader=True)

Try running this app yourself. And see if you get something that looks like this:

Conclusion

So we've just about hit our limit for how much craziness we can sanely cram into a web app that consists of a single file. The final example in this exercise is way messier than what you will be creating in the real world…because in the real world, you won't be cramming everything into a single file.

If you came out of this confused, it's OK – there are several months, if not years worth of programming, design, and web architecture concepts that we mostly gloss over.

Going beyond iframes

Thinking back to our specific web application, which made use of YouTube's embed code, one thing that you might have felt is how limited we were in dealing with YouTube content: we can basically determine what video we want to play, the size of the viewer, and whether it should autoplay, among other simple options.

However, we couldn't do something as basic as pull out the video title, which is why our HTML template contains code like this, in which we can only display a YouTube video by ID:

"""<a href="{url}">YouTube video: {id}</a>""".format(url=youtube_url, id=vid)

More importantly, we don't have the ability to query YouTube for available video titles. Instead, our users have to already know the YouTube ID of the video that they want to see on our crazy web app; else, they get rick-rolled.

Wouldn't it be nice to be able to conduct a programmatic search from our site for YouTube videos? Or even have an "official" way to tell if a video ID is valid, rather than our generic HTTP status-code-checking function?

These are all reasons why sites like YouTube provide an API, which is significantly more complicated to use than an embed code. But the tradeoff is much more functionality.